A team of researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Brookhaven National Laboratory has successfully engineered poplar trees to produce a key industrial chemical that can be utilized in the creation of biodegradable plastics. This groundbreaking study, published on November 20, 2025, in the Plant Biotechnology Journal, highlights the potential of modified trees to serve as sustainable sources for valuable materials.

The engineered poplar trees exhibit enhanced tolerance to high salt levels in soil, making them easier to convert into biofuels and other bioproducts. The implications of this research extend to establishing a more flexible domestic supply chain, which could ultimately lower costs and reduce reliance on imported specialty chemicals.

Chang-Jun Liu, a biologist at Brookhaven Lab and the study’s lead researcher, emphasized the significance of this work: “This study demonstrates the metabolic ‘plasticity’ of poplar and the feasibility of engineering stress-resistant crops to produce multiple desired products.” The collaborative research involved partners from the Joint BioEnergy Institute, managed by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, and Kyoto University.

Innovative Genetic Modifications

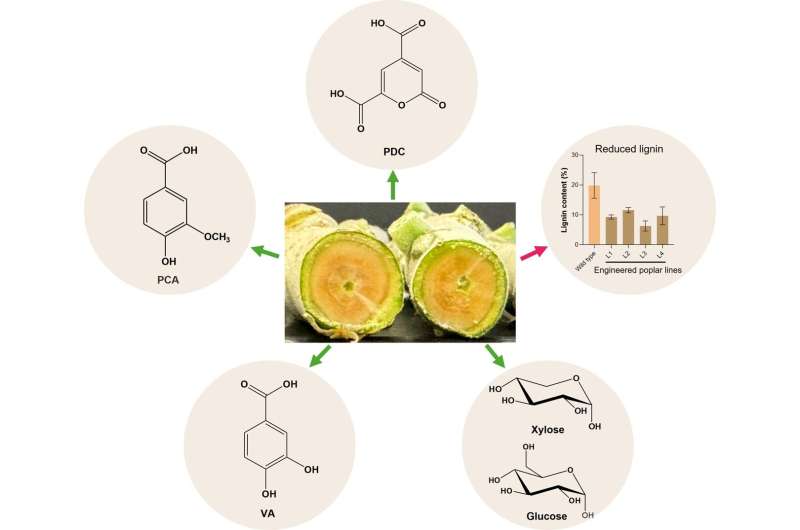

The team focused on modifying hybrid poplar trees to produce 2-pyrone-4,6-dicarboxylic acid (PDC), a compound integral to creating durable, high-performance plastics and coatings. Traditionally, PDC has been synthesized through complex chemical processes or by employing bacteria to decompose biomass. By introducing five genes from naturally occurring soil microbes into the poplar trees, the researchers established a synthetic metabolic pathway that enables the plants to produce PDC along with other useful compounds like protocatechuic acid and vanillic acid.

According to Nidhi Dwivedi, a member of Liu’s team, “Poplar grows quickly, adapts to many environments, and is easy to propagate. By adding this new pathway, we’re expanding the range of bioproducts these trees can produce.”

Enhanced Biomass Properties

The genetic modifications also positively impacted the internal chemistry of the poplar trees. The engineered varieties showed reduced lignin levels—an organic polymer that complicates biomass breakdown—while increasing hemicellulose content, a type of complex sugar valuable for biochemical conversions. These changes resulted in yields of up to 25% more glucose and 2.5 times more xylose, crucial components for biofuels and other bioproducts.

Additionally, the modifications led to an increased accumulation of suberin, a waxy substance that protects plant tissues, aids in water and nutrient retention, and inhibits toxins. This allows the modified poplar trees to thrive in less-than-ideal conditions, such as saline soils. Dwivedi noted, “These trees can grow on soil not suitable for food production, so they won’t compete for prime agricultural land. When they are stressed by high salt levels, they produce even higher levels of bioproducts than when they are not stressed.”

Currently, the results have been observed in greenhouse settings. The next phase of research will involve testing the engineered poplars under field conditions to validate their performance and long-term stability. The team aims to optimize the metabolic pathway further to increase yields of PDC and related compounds.

This innovative model for plant-based manufacturing offers adaptability to meet evolving demands and requires less upfront investment compared to traditional chemical manufacturing facilities. Liu concluded, “This work gives us a deeper understanding of plant metabolism. Using different combinations of genes, we can potentially make additional products. This knowledge will help researchers design productive crops for a range of U.S. manufacturing and agricultural needs.”

The findings from this research hold promise not only for the production of biodegradable plastics but also for creating a sustainable approach to meet future industrial demands.