Radio astronomy faces challenges from the growing number of satellites in orbit, particularly those located in geostationary positions. A recent study led by researchers from the CSIRO Astronomy and Space Science division has examined radio emissions from these satellites, which orbit approximately 36,000 kilometers above Earth. Their findings, published on December 15, 2025, indicate a largely positive outlook regarding interference in critical frequency ranges used by astronomers.

Geostationary satellites maintain a fixed position relative to the Earth, making them ideal for various applications, including television broadcasts and military communications. Unlike low Earth orbit satellites that move rapidly across the sky, these satellites can remain in a telescope’s field of view for extended periods. This makes them particularly relevant for radio astronomy, where even small emissions can disrupt sensitive observations.

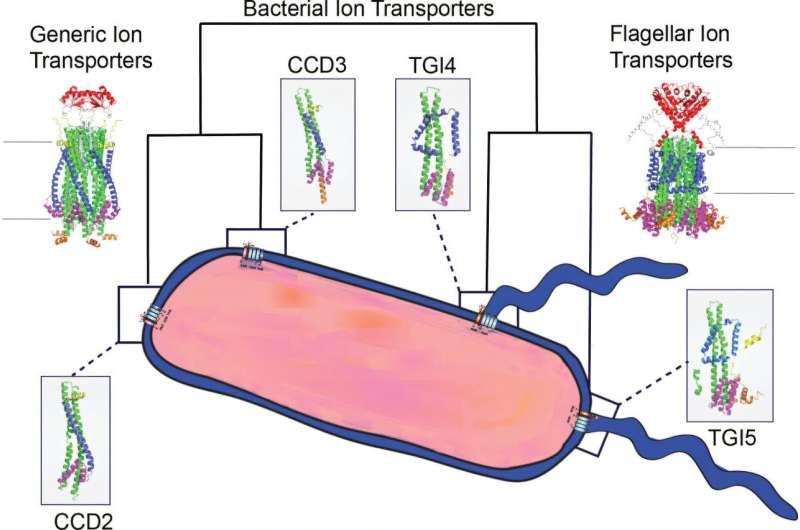

Utilizing archival data from the GLEAM-X survey, conducted by Australia’s Murchison Widefield Array in 2020, the research team analyzed frequencies between 72 MHz and 231 MHz. They focused on tracking up to 162 geostationary and geosynchronous satellites over a single night. The researchers employed stacking techniques to enhance their ability to detect any radio emissions from these satellites.

The study revealed that most of the observed geostationary satellites did not emit detectable radio signals at the examined frequencies. The team established upper limits of emissions, with most satellites registering below 1 milliwatt of equivalent isotropic radiated power within a 30.72 MHz bandwidth. The best measurements achieved a remarkably low threshold of 0.3 milliwatts. Only one satellite, Intelsat 10–02, exhibited a potential emission of around 0.8 milliwatts, still significantly lower than the emissions typically observed from low Earth orbit satellites, which can emit hundreds of times more power.

These findings are crucial as they establish a baseline for future radio frequency interference assessments. The Square Kilometer Array, set to be one of the most sensitive radio telescopes upon completion, will operate in the same low frequency range. As satellite constellations increase and current radio telescopes become more sensitive, preserving a “radio quiet” environment for astronomical observations is becoming increasingly critical.

The research underscores the importance of monitoring emissions from satellites. While geostationary satellites currently appear to be compliant with radio frequency regulations, the evolution of technology and a rise in satellite traffic could pose new challenges. The potential for unintended emissions, even from satellites designed to minimize interference, highlights the need for ongoing vigilance in this area.

This study not only contributes to the understanding of radio emissions from distant satellites but also serves as a warning about the future of radio astronomy. As the landscape of satellite communications continues to evolve, maintaining the integrity of astronomical observations will require careful management and monitoring of radio frequencies.

For further details, refer to the research paper: S. J. Tingay et al, “Limits on Unintended Radio Emission from Geostationary and Geosynchronous Satellites in the SKA-Low Frequency Range,” available on the arXiv preprint server.