Astronomers face a growing challenge as satellites orbiting the Earth contribute to radio frequency pollution. A recent study led by researchers from the CSIRO’s Astronomy and Space Science division has provided significant insights into the radio emissions from geostationary satellites located approximately 36,000 kilometres above the Earth. This research is crucial as these satellites increasingly interfere with the frequencies used for astronomical observations.

While much attention has been given to low Earth orbit satellites like those in SpaceX’s Starlink constellation, geostationary satellites represent a different concern. These satellites maintain a fixed position relative to the Earth, making them essential for various applications, including television broadcasts and military communications. Unlike their low orbit counterparts, which move quickly across the sky, geostationary satellites can linger in the field of view of telescopes for extended periods.

New Findings on Radio Emission Levels

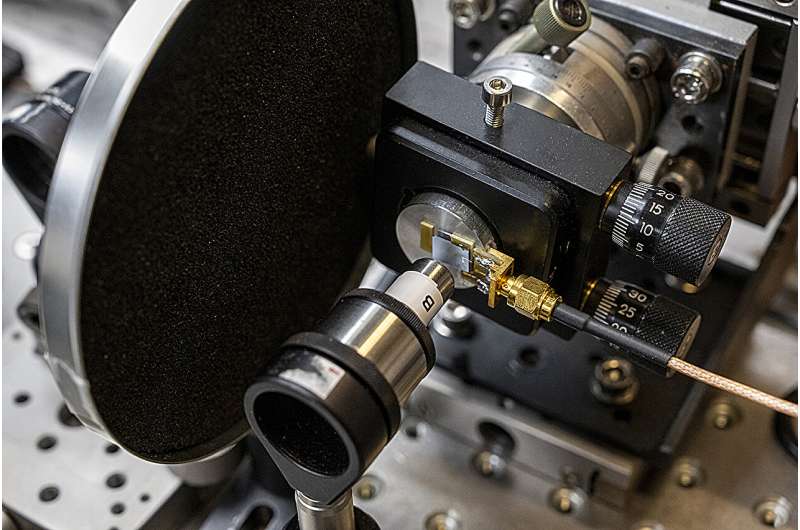

Until now, there had been no systematic measurement of radio emissions from these distant satellites. The research team utilized archival data from the GLEAM-X survey, collected by Australia’s Murchison Widefield Array in 2020. They focused on frequencies between 72 to 231 megahertz, which are critical for the upcoming Square Kilometre Array. This extensive analysis tracked up to 162 geostationary and geosynchronous satellites over the course of a single night.

The results indicate that the majority of these satellites do not emit detectable radio emissions at the frequencies that are vital for astronomical studies. For most of the satellites observed, the researchers established upper limits of radio emissions at less than 1 milliwatt of equivalent isotropic radiated power within a bandwidth of 30.72 megahertz. The most impressive findings showed limits as low as 0.3 milliwatts. Only one satellite, Intelsat 10-02, displayed a potential detection of unintended emissions at approximately 0.8 milliwatts. Even this satellite’s emissions were significantly lower than those typically seen from low Earth orbit satellites, which can emit hundreds of times more power.

Impact on Future Observations

The implications of these findings are significant, particularly as the Square Kilometre Array will be far more sensitive than existing instruments. The design of the study, which involved pointing the telescope near the celestial equator, allowed each satellite to remain in view for extended periods. This method enabled the researchers to employ sensitive stacking techniques capable of detecting even intermittent emissions.

As satellite technology continues to evolve and the number of satellites in orbit increases, the pristine radio quiet that astronomers have relied upon for decades is at risk. Even satellites designed to avoid certain protected frequencies can inadvertently leak emissions through various systems, including electrical components and solar panels.

For the time being, geostationary satellites appear to be considerate neighbors within the low frequency spectrum. However, as the landscape of satellite communications changes, the question remains whether this trend will continue. The new measurements serve as crucial baseline data for predicting and mitigating future radio frequency interference. With the potential for increased satellite traffic, understanding these emissions will become ever more vital for the astronomical community.