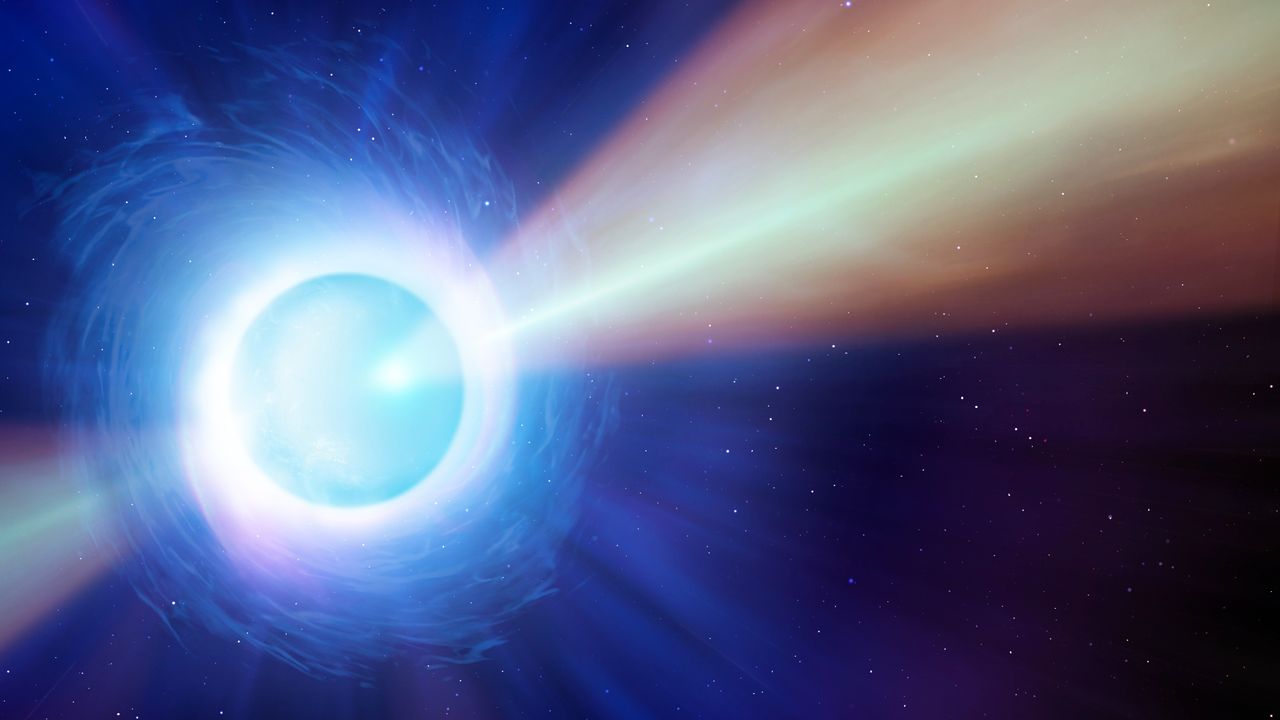

Astronomers at the SETI Institute have made significant advancements in understanding how interstellar space affects radio signals. Their research focuses on the pulsar PSR J0332+5434, revealing that gas between stars can distort radio signals by billionths of a second. This distortion, while imperceptible to humans, is crucial for experiments relying on pulsars as precise cosmic clocks, which are essential in the search for extraterrestrial intelligence and low-frequency gravitational waves.

The study, led by Grayce Brown, began in late February 2023 and involved nearly daily observations over a span of ten months using the Allen Telescope Array in California. The team monitored changes in the pulsar’s radio signals, which are located over 3,000 light-years from Earth. Through approximately 400 observations, they detected variations in the pulsar’s scintillation pattern, which refers to the twinkling effect caused by the interaction of radio waves with interstellar gas.

As the radio waves emitted from the pulsar travel through space, they encounter clouds of charged gas, primarily free electrons. This interaction causes the radio waves to bend and scatter, resulting in slight timing delays of the signals. According to the study, these discrepancies can range from tens of nanoseconds, which, although minute, can significantly impact the detection of faint gravitational waves.

In essence, pulsar timing arrays depend on synchronized pulse arrival times to identify low-frequency gravitational waves. If the effects of interstellar gas are not accurately accounted for, they may obscure or mimic the signals researchers are trying to detect, potentially leading to erroneous conclusions. Brown emphasized the importance of understanding scintillation patterns: “Noticeable scintillation can help SETI scientists distinguish between human-made radio signals and signals from other star systems.” This capability is vital, as it allows researchers to better differentiate between terrestrial noise and genuine cosmic signals.

The observations were part of a comprehensive effort to monitor about 20 pulsars over a year, following a pilot phase in late 2022. Although the team did not identify a consistent pattern in scintillation changes, the results pave the way for future campaigns that may refine predictions and improve adjustments for interstellar distortion. The findings were published in The Astrophysical Journal on December 10, 2025.

Brown noted, “Because of this research, we know how much scintillation to expect from a radio signal traveling through this pulsar’s region of interstellar space.” She added, “If we don’t see that scintillation, then the signal is probably just interference from Earth.” This research not only enhances our understanding of pulsar dynamics but also contributes significantly to the broader field of astronomy, reinforcing the ongoing quest to uncover signs of intelligent life beyond our planet.