A recent study published in *Nature* has unveiled significant insights into the formation of planets in a young star system known as V1298. Located in the Taurus constellation approximately **350 light years** away from Earth, V1298 is just **30 million years old** and hosts four unique planets described as “cotton candy” due to their large size and low density. This research, led by **John Livingston** from the **National Astronomical Observatory of Japan**, highlights a pivotal stage in planetary development.

The planets in the V1298 system are comparable in size to **Jupiter**, yet they exhibit much lower mass. One of these planets, measuring about five times the size of Earth, has a density similar to that of a marshmallow. The least dense planet in the system possesses an astonishing density of just **0.05 g/cm³**, resembling cotton candy. Prior estimates of their masses were significantly inflated, ranging from **200 to 300 times** more than the newly calculated figures. This discrepancy stemmed from the youthful characteristics of V1298’s star, which is known to be active, featuring sunspots and frequent flares that can mimic the signals sought by exoplanet hunters.

To refine their mass estimates, the research team employed data collected over **nine years** from various telescopes, including **Kepler**, **TESS**, **Spitzer**, and the **Las Cumbres Observatory**. They utilized a method known as transit-timing variations (TTVs), which tracks the timing of a planet’s transit in front of its star, accounting for gravitational influences from other nearby planets. This approach not only provided more accurate mass measurements but also allowed researchers to recover one planet previously deemed “lost” due to an inability to determine its orbital period, which is approximately **48.7 days**.

Understanding the mass and characteristics of these newly formed planets is crucial for placing their discovery within the broader context of exoplanet evolution. Two main categories of exoplanets dominate observations: **Super-Earths**, typically rocky and no more than **1.5 times** the radius of Earth, and **Sub-Neptunes**, which are larger and more gaseous, often reaching **2.0 times** Earth’s radius. Both types are usually found in close orbits around their stars, closer than Mercury in our solar system, possibly due to the ease of tracking their rapid orbital periods.

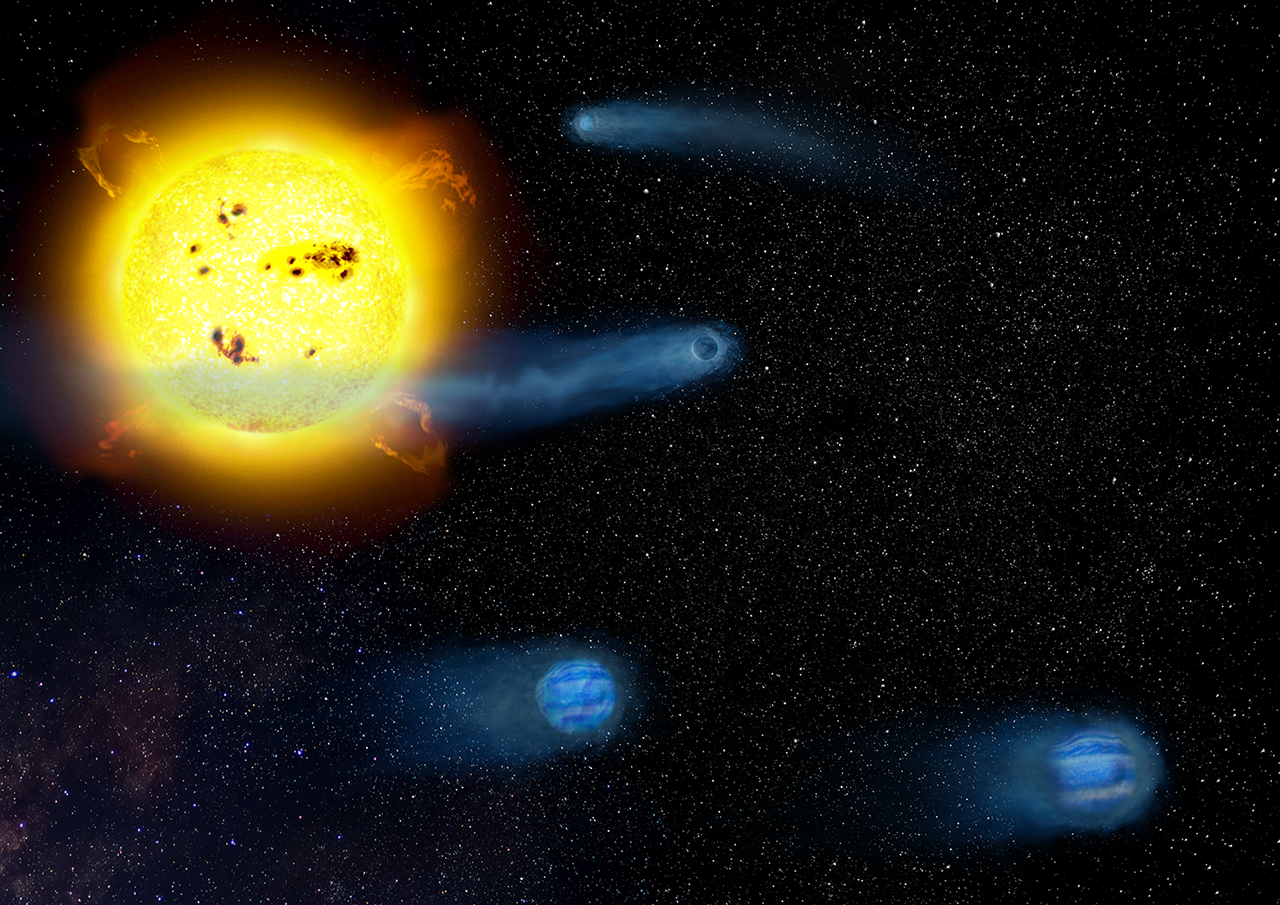

The V1298 system presents a model for how these distinct types of exoplanets can evolve over time. Astronomers generally agree that as the planets age, they are likely to lose their atmospheres, a process that could occur through mechanisms such as photoevaporation—where radiation from the host star strips away the atmosphere—or through internal heat pushing the atmosphere outward. This latter process can take billions of years.

Interestingly, the paper introduces a third mechanism termed “boil-off,” which occurs when a protoplanetary disk, acting as a pressure lid, dissipates. This allows a planet’s atmosphere to expand outward rapidly, akin to steam escaping from a pressure cooker when the lid is removed. While other systems, such as **Kepler-51**, have provided evidence of similar processes, V1298 stands out due to its youth, offering researchers a critical window into the earlier stages of planetary formation.

The significance of this study is underscored by its acceptance in *Nature*, a premier academic journal. The extensive data collection over nearly a decade emphasizes the importance of these findings, which may serve as a milestone in the field of exoplanetary research. Future investigations may uncover even younger star systems within existing exoplanet datasets, potentially revealing further clues about the processes governing planet formation.

As research continues, the insights gained from the V1298 system will enhance our understanding of how planets evolve and adapt in diverse environments throughout the galaxy.