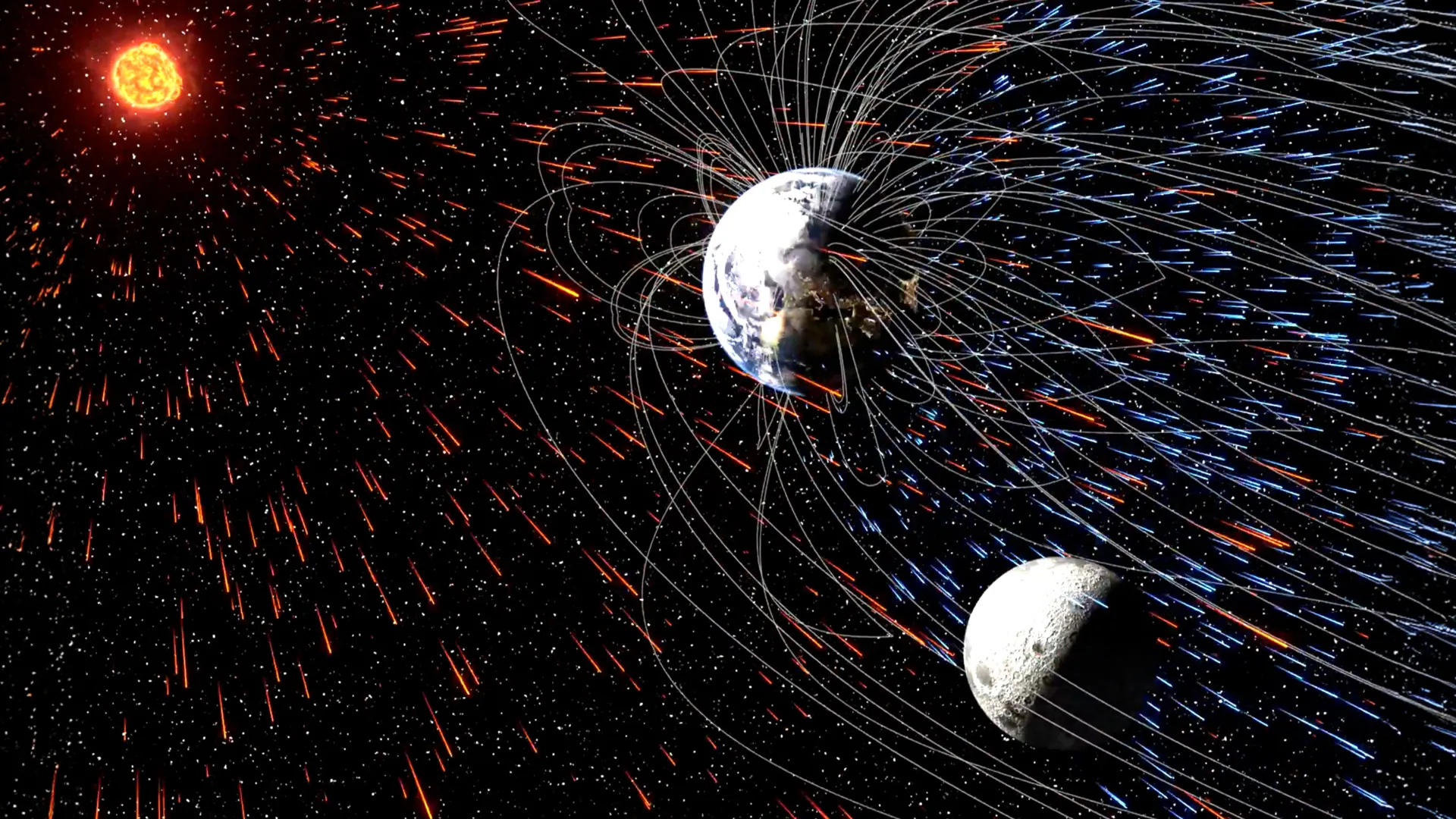

Tiny fragments of Earth’s atmosphere have been journeying to the moon for billions of years, propelled by Earth’s magnetic field, according to new research from the University of Rochester. This groundbreaking study, published on January 5, 2026, in the journal Nature Communications Earth and Environment, suggests that rather than acting as a barrier, the magnetic field has actually facilitated the transfer of atmospheric particles to the lunar surface.

The moon has long been perceived as a barren and lifeless entity, but this new understanding reveals a more intricate narrative. For eons, microscopic pieces of Earth’s atmosphere have reached the moon, embedding themselves in its soil. These materials could potentially support future human activities on the lunar surface.

Researchers were previously uncertain about the mechanisms allowing these particles to travel such vast distances over geological timescales. The study led by Eric Blackman, a professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Rochester, provides clarity. Blackman noted, “By combining data from particles preserved in lunar soil with computational modeling of how solar wind interacts with Earth’s atmosphere, we can trace the history of Earth’s atmosphere and its magnetic field.”

The findings indicate that the moon may serve as a long-term archive of Earth’s atmospheric history. This insight raises the prospect that the moon could harbor valuable resources for astronauts working on its surface in the coming years.

Insights from Apollo Samples

The research draws heavily on samples collected during the Apollo missions in the 1970s. Analysis of these samples revealed that the moon’s surface layer, known as regolith, contains volatile substances such as water, carbon dioxide, helium, argon, and nitrogen. While some of these materials clearly stem from the solar wind—a continuous stream of charged particles emitted by the sun—the quantities found, particularly nitrogen, exceed what could be explained by solar wind alone.

In 2005, scientists from Tokyo University proposed that part of these volatiles originated from Earth’s atmosphere. They suggested that this transfer must have occurred early in Earth’s history, before the planet developed a magnetic field. Their premise was that once the magnetic field formed, it would inhibit atmospheric particles from escaping into space.

The University of Rochester team, however, reached a different conclusion. They conducted advanced computer simulations to understand how atmospheric particles might travel from Earth to the moon. The research team included Shubhonkar Paramanick, a graduate student and Horton Fellow at the Laboratory for Laser Energetics, along with John Tarduno, the William R. Kenan Jr. Professor in Earth and Environmental Sciences, and Jonathan Carroll-Nellenback, a computational scientist at the Center for Integrated Research Computing.

Their simulations explored two scenarios: one with an early Earth lacking a magnetic field and a stronger solar wind, and another representing modern Earth with a robust magnetic field and a weaker solar wind. The findings demonstrated that particle transfer to the moon is significantly more efficient in the present-day model.

The solar wind can dislodge charged particles from Earth’s upper atmosphere. These particles then follow the magnetic field lines that extend into space, intersecting the moon’s orbit. Over billions of years, this process acts like a slow funnel, gradually allowing small amounts of Earth’s atmosphere to settle onto the lunar surface.

A Historical Record and Future Resources

The continuous exchange between Earth and the moon implies that lunar soil may hold a chemical record of Earth’s atmospheric history. Studying this soil could provide scientists with valuable insights into the evolution of Earth’s climate, oceans, and potentially life itself over billions of years.

Moreover, the findings indicate that the moon may contain more useful materials than previously assumed. Volatile elements such as water and nitrogen could be crucial for sustaining long-term human activity on the moon. This would reduce the need for supplies shipped from Earth, enhancing the feasibility of future lunar exploration.

“Our study may also have broader implications for understanding early atmospheric escape on planets like Mars,” said Paramanick. “Mars lacks a global magnetic field today, but it likely had one similar to Earth in the past, along with a thicker atmosphere.” By examining planetary evolution along with atmospheric escape through different epochs, researchers can gain insights into how these processes affect planetary habitability.

This research was supported by funding from NASA and the National Science Foundation. As scientists continue to explore the moon’s potential, these findings could pave the way for a deeper understanding of not just our lunar neighbor, but also the broader cosmos.