A team of researchers from MIT has unveiled a groundbreaking material capable of transforming into various three-dimensional structures with a simple pull of a string. This innovative development draws inspiration from the Japanese paper art technique known as kirigami, which involves cutting and folding paper to create intricate designs. The findings, detailed in a recent paper published in ACM Transactions on Graphics, highlight the potential for applications ranging from portable medical devices to modular habitats for future missions to Mars.

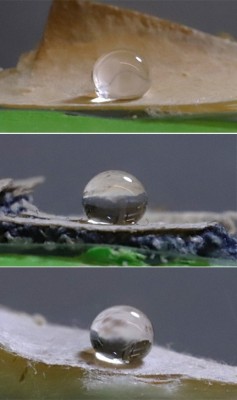

The material begins as a flat grid of quadrilateral tiles, seemingly unremarkable at first glance. However, by pulling a small string attached to the grid, the tiles morph into the desired 3D shape. The researchers employed an algorithm that translates user-defined 3D structures into a flat layout, mimicking the cutting techniques used in kirigami. This approach encodes the material with specific properties, allowing it to change shape efficiently.

At the core of this technology is an auxetic mechanism, which enables the material to become thicker when stretched and thinner when compressed. This unique property aids in the transformation process, ensuring smooth transitions between shapes. The algorithm optimizes the path of the string to minimize friction, making the actuation process straightforward.

“The simplicity of the whole actuation mechanism is a real benefit of our approach,” stated Akib Zaman, the lead author of the study and a graduate student at MIT. “All they have to do is input their design, and our algorithm automatically takes care of the rest.”

After extensive simulations, the team successfully created several practical objects, including medical tools such as splints and posture correctors. They also designed igloo-like structures. Notably, the algorithm is adaptable to various fabrication methods. The researchers demonstrated this by using laser-cut plywood to construct a fully deployable, human-sized chair, which was able to support weight effectively.

Despite the promising results, the researchers acknowledged potential “scale-specific engineering challenges” for larger structures. Nevertheless, the ease of use and accessibility of this new method has prompted the team to explore solutions for these challenges, as well as the creation of smaller structures.

“I hope people will be able to use this method to create a wide variety of different, deployable structures,” Zaman expressed, reflecting the team’s enthusiasm for future applications of their innovative material. As this research progresses, it could pave the way for revolutionary designs in architecture, healthcare, and beyond.